Taste all the way down

Part 1 in a collaborative series about taste and science

Oscillator and The Hard Thing are blogs by people who have spent many years thinking together about the applications and implications of new technologies in the business of biology. We’re teaming up for a series of posts about AI, biotech, and the ineffable magic of taste.

The taste to know when something is wrong

In 2002, Michael Crichton gave a lecture bemoaning the state of the media and its tendency to focus on speculation over facts. He shared an anecdote from a conversation with the physicist Murray Gell-Mann about how we notice when these speculations miss the mark in our own areas of expertise, but forget that fallibility outside of our domain.

“Briefly stated, the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect is as follows. You open the newspaper to an article on some subject you know well…You read the article and see the journalist has absolutely no understanding of either the facts or the issues. Often, the article is so wrong it actually presents the story backward—reversing cause and effect. I call these the ‘wet streets cause rain’ stories. Paper’s full of them.

In any case, you read with exasperation or amusement the multiple errors in a story—and then turn the page to national or international affairs, and read as if the rest of the newspaper was somehow more accurate about Palestine than the baloney you just read. You turn the page, and forget what you know.”

We’ve all experienced this “Gell-Mann Amnesia” in some form. You read a news article about your employer and groan about how they just fundamentally misunderstood basic facts about the company, concluding that they are clueless. But a week later you gleefully read the same author’s teardown of your main rival. This behavior is both perfectly rational – when we lack expertise, even imperfect information feels highly additive – and entirely irrational – presumably that source has a similar error rate across the topics about which they are opining.

In the age of AI, this phenomenon takes on a new dimension and level of urgency. AI can give detailed, thoroughly researched and cited answers to any question we can dream up. It appears to be the most patient and well-read of teachers, a fount of knowledge that shares brilliant insights with thorough background. In our own areas of expertise, we notice immediately the gaps in logic, the missing context, and when things are not quite right. Yet we forget this lack of nuance as soon as we change context and the pattern repeats.

We hear the excited speculation every day about the incredible things AI will have accomplished in ten years. Then we notice the groans and eyerolls from the people who have been working in that particular field for a long time. Are they just protecting their turf, holding onto the last scraps of power they have as human experts? Or does this “GPT-Mann Amnesia” show us something more fundamental about how we work together and what’s needed to solve hard problems with AI?

Raising the floor

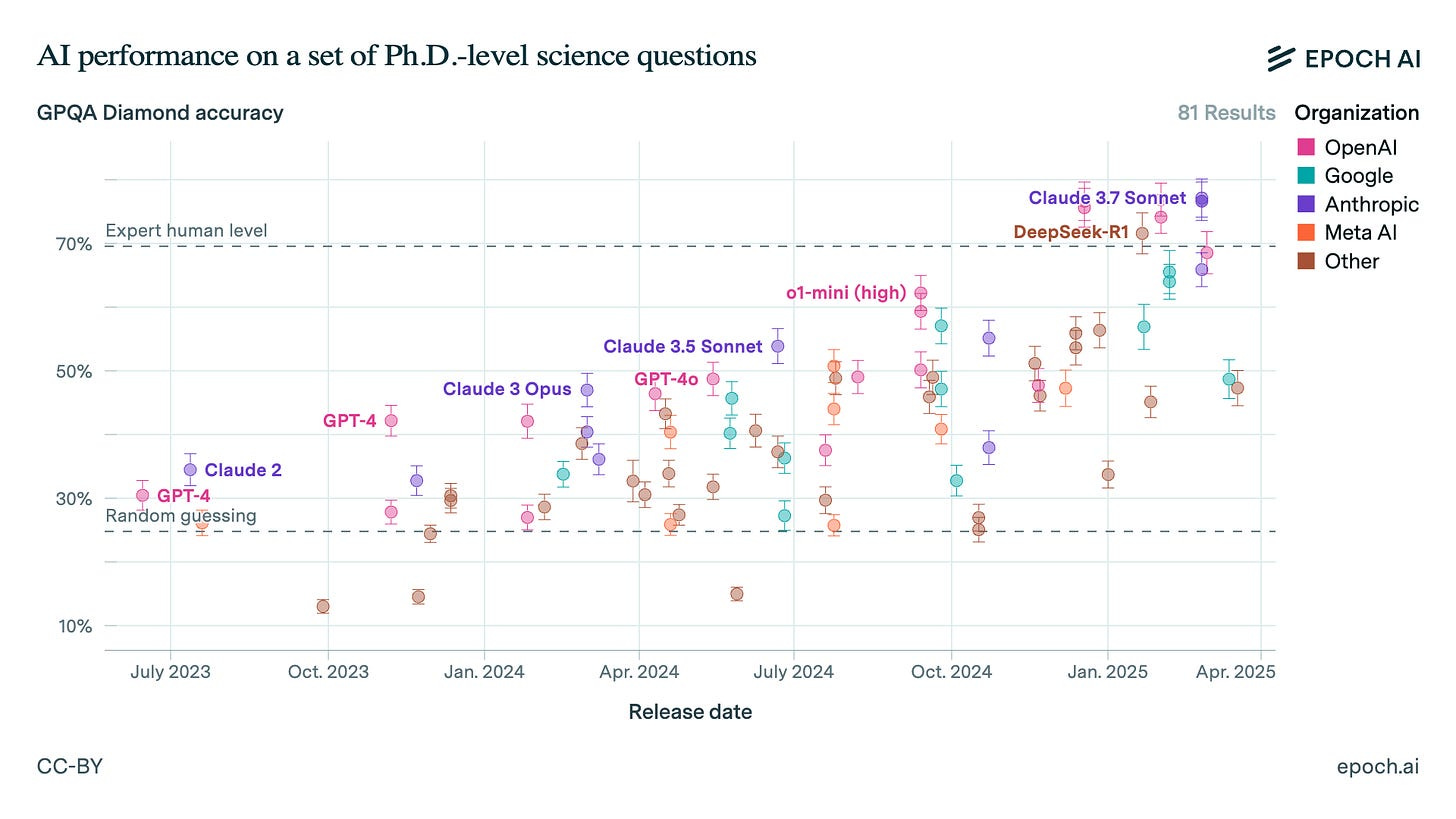

The latest AI models are outperforming PhDs on multiple-choice science questions. They have ingested all the knowledge that has ever been written down into their training sets. Competence has been commodified.

But the work of a scientist looks nothing like answering multiple choice questions. The real work begins where existing knowledge ends. What are good questions to ask? What are interesting and promising new hypotheses to pursue? What is the right technique to try in this experiment? What is the craft required to set up that experiment and interpret its results?

These are critical questions for doing good science, but they are difficult to assess and benchmark, and thus we largely ignore them when we measure AI’s “intelligence”. These questions belong to the domain of taste—the discernment, trained over time, to pick the right trend, the right question, the right information. But the data that trains human taste is often tacit: understood without being stated or written down explicitly. This subconscious intelligence does not show up in AI training sets and therefore remains out of reach of our models.

Taste, developed through experience, changes how we evaluate and use the information we see in the news and the answers and designs generated by AI. Beyond the phenomenon of Gell-Mann Amnesia, where an expert has the taste to determine whether the information is good, taste also defines what someone does with the information. While AI can help us find and format facts, doing something truly useful with that information requires different skills as well as taste and significant amounts of expertise or tacit knowledge.

A somewhat trivial recent example: a couple months ago, frustrated by the lack of good, comprehensive resources in the emerging industry at the intersection of AI and Bio, Anna Marie created and published a little database of companies in the space. It only took a couple days to create, arguably anyone could have done it much better with a bit of vibecoding, but it created what felt like an outsized response from the community (a common reply: “you just saved me 6 months of research, thank you!!”).

In a world where information is freely and seemingly infinitely available, applying a small amount of taste (decent intuition about the types of information we might want to understand about a company and how we might want to manipulate that data) and expertise (some rusty coding skills) made all the difference.

Since publishing the database, there have been many more mature efforts, including a Gossett database of 8,000+ (!!!) biotech companies, a relay.app tool to run competitive research, this one-prompt table built by Claude 3.7 and likely hundreds of other tools that we haven’t seen yet. The ceiling became the floor and the floor was raised for everyone. We’re now flooded with tools that once required some taste to create and once again need taste and intuition to use in a differentiated way.

Packy McCormick’s concept of “Hyperlegibility” captures this phenomenon well. With infinite sharing and access to information, what’s to be done? Who wins?

“Hyperlegibility isn’t good or bad. It’s neither and both. But it certainly is. Information used to be the highest form of alpha. Now everyone bends over backwards to leak it….We are game theoretically driven to share more and more of our best ideas, the ones that we might have once exploited in silence....

The question to ask is: assuming Hyperlegibility, what do I do?...There’s something about the growing relative importance of relationships, of “having a guy,” of agency and the ability to get things done."

The internet, and now AI, have promised and delivered on the democratization of knowledge and information. These tools have challenged the power of the gatekeepers and institutions that have long been the stewards and distributors of information, and the arbiters of good work and truthful knowledge. But ironically, as our technologies have challenged the power of those who hold knowledge, they have served to reinforce the power of those who hold the experience and skill to choose and curate, those with judgement, relationships, and the most elite of distinctions, good taste.

Taste all the way down: Drug hunters, magic hands, and the small things that matter

“Taste” has a lot of cultural baggage. We usually talk about taste to distinguish not just lived experience, but often what people consider to be the “right” experience. When we think of taste, we might think of high-brow sommeliers, art curators, or high fashion. “Good taste” is therefore often a marker of class as much as it is a sign of expertise, and works to signal a person’s inclusion or exclusion from different levels of a hierarchy.

There is a similar kind of class structure at work when people talk about “taste” in the sciences. Good scientific taste marks the top labs and Nobel prize winners, who persisted in following a particular set of questions with methods and insights that set them apart. Likewise, elite “drug hunters” in the top pharma companies are described as having good taste (which could never be automated with AI). They can sniff out good candidates, carefully balancing a range of considerations, from the market potential to manufacturing considerations. They can identify when the data is just right and what to do with it.

But taste isn’t just about fancy stuff and big ideas. Taste goes all the way down. The same quality we admire in drug hunters shows up just as much at the bench in every process and protocol. It's the technician who notices a gel polymerizing a bit too quickly and remakes it before running a Western blot; the biologist who discards a cell line because the cells "just don't look happy"; the chemist who senses a reaction is off-track because the stir bar is clicking against the flask. It’s the scientist who annoys her postdoc because she is so careful and slow with her experiments but then publishes reproducible results a year before anyone else in the field because she rarely has to re-work an experiment. These small, often sensory intuitions—the "magic hands" of the lab—often make the difference between a breakthrough and weeks wasted troubleshooting.

It is often these incredibly skilled people who are “the guy” we call to get something done. We’ve heard stories of large pharma CEOs traveling the globe to identify the people on their teams whose “magic hands” are the key to reproducing critical experiments, so essential are they for success. But despite recognizing the importance of this "by-hand" labor, a lot of the narrative of contemporary science-focused technology is about not “wasting” time with “manual” labor. Scientists, they say, should spend their time cultivating tasteful ideas, not magic hands.

Ironically, by wanting to elevate scientists out of the realm of manual labor in order to speed up science, we may actually be slowing things down by not noticing or valuing the small things that can have a big impact. These matters of taste, deep intuitions, and frustrating lessons gained through experience at the bench—which brand of reagent or plastic dishes, how vigorously to swirl a culture, the precision and pace of a critical experimental step—are passed down as oral histories in particular labs, one way that hierarchies and successful pedigrees are maintained. They move person to person and experiment to experiment during scientific training, sometimes completely intuitively, and rarely written down in a paper or protocol. We are incentivized to publish that Nature paper showcasing the eureka moment and novel result, not the months and years of painful trial and error to get there. But this makes reproducing, automating, and getting lasting value from that discovery much harder.

To raise the floor in science, we have to understand how this knowledge is learned and the lessons that we can bring to other experiments when we pay attention to it. Making this level of taste more accessible—raising the floor—may make future application of those ideas more accessible, where taste and expertise can continue to raise the ceiling.

The Endless Frontier?

In 1945, Vannevar Bush wrote Science: the Endless Frontier, arguing that investing in fundamental, curiosity-driven scientific research is critical to driving technological innovation, economic prosperity, and national security. Yet today, many are arguing that the institutions and systems set up by Bush and his contemporaries have stalled, and we've entered an era of stagnation marked by incremental improvements rather than transformative breakthroughs. While we’ve benefited from enormous technical progress in the last century, major leaps in fundamental science seem less frequent and breakthroughs feel increasingly elusive. We’ve lost the drive to the frontier.

In response, many argue that advances in artificial intelligence will restart this engine and drive us toward a post-scarcity economy, in which the marginal cost of information and intelligence approaches zero and breakthroughs therefore become commonplace.

But we’ve seen that access to information is only one dimension required for creating something of value. Whether it’s having the judgement to know what information to really trust and act on, what questions to ask, who to call, or how to design the right experiment, using knowledge and intelligence is the domain of taste.

The endless frontier belongs in the desirable upper right hand quadrant of a two by two matrix that reflects both of the dimensions required to make new knowledge and new technology:

the ability to use new tools to navigate and access information, and

the judgement and taste to know what to do with it

Some of our most seasoned experts today struggle with using the new tools for accessing intelligence and information. And the scrappy engineers who can pull vast amounts of information together with a swarm of AI agents while they sleep often struggle to translate that information into valuable solutions. The winners will be the people and organizations who can do both.

For people who specialize in one axis, the need for both can be destabilizing. People building new automation and AI ignore the messy reality and lived experience of the people they are automating at their peril. But likewise, in science we find many who fiercely guard their hard-won “tricks of the trade.” To keep driving into the top right quadrant, we have to make that knowledge less implicit and more widely accessible. When tough lessons turn into taste that distinguishes the few who possess it, we lose much of the momentum that allows us to keep raising the ceiling. When we limit access to these techniques, we stumble in building the complexity needed to drive innovation and this hard-earned knowledge becomes scattered when R&D teams are dismantled, its impact never realized.

We stand at an inflection point. The resources available and opportunities ahead of us are unlike anything that has come before. But also because complacency carries profound risk for individuals, organizations, and even nations slipping into fringe influence at best.

The rise of AI, despite all its limitations, has made competence instantly accessible, raising the floor and forcing us to redefine what constitutes genuine expertise. It has amplified both our strengths and shortcomings, revealing more clearly than ever the immense value of judgment, intuition, and taste it takes to raise the ceiling.

By prioritizing the hard, often unscalable work of building judgment, intuition, and scientific craftsmanship into our systems, labs, and training, we raise both the floor and ceiling of what's possible. The pace at which the ceiling on taste rises is the pace at which the endless frontier moves.

I wrote my comment in The Hard Thing! Hopefully you can combine the discussions somehow.

Brilliant! Love this.